Cory Lemke moved back to Korea in 2013, shortly after graduating from Arizona State University. Since then, he’s met his birth family, lived and worked in his birth town of Jeonju, and started his own English instruction business based in the Yeoksam neighborhood on the bustling east side of Seoul.

Lemke, who studied political science, is also the Vice Chairperson of Democrats Abroad Republic of Korea and Co-Chair of the Asian American Pacific Islander Caucus. “Organizing, education – they’re my passion,” he says. “I believe in bringing the community together.”

Now living in Seoul, Lemke, 29, shared some stories about life in Korea, meeting his birth family, and if he ever thinks he’ll run for public office.

The following Q&A has been condensed and edited.

Please introduce yourself. Can you start from the beginning?

I was adopted to Northern Iowa. I have an older sister, older brother, and younger sister. My older brother and younger sister are also adopted from Korea. We grew up maybe 20 minutes from the Minnesota-Iowa border in a town of about 500 people.

When I was in middle school, we moved to Tucson, Arizona. Much more diverse. I went to high school, then ASU (Arizona State University), then went to the University of Arizona for my master’s in international relations. After I graduated, I decided to move to Korea.

As an adoptee, how did you feel about returning and now living in Korea? Has your perspective changed since being here?

Having been here for almost eight years now, it’s fluctuated over time. I think being here has really helped change that perspective. I think when I first got here, I was a little bit more aggressive about fitting into Korean society.

I think the most striking thing for me, having seen people come and go and do their searches and be here, is that everyone’s story is unique. I think a lot of the [adoptee] community is trying to find an answer, like, this is what happened. I think it’s important from a certain point of view to understand what happened in some cases. But there’s so much diversity within the community in terms of story and I don’t think you can say one size fits all regarding our stories and our relationship to adoption.

As an American, I think we try to project our American experience on the Korean experience. That can be problematic. What comes to mind in my personal story is that I’m thankful for my life and where I’ve ended up. But I recognize that that’s probably not a universal sentiment.

With the perspective of hindsight, how do you view your younger self now? The one who came to Korea in 2013.

My personality is the same. But it’s, I think, the outlook towards adoption. I’m not as angry at the system. I think there are problems with the system. But I do think, at least in my own personal story, everyone was trying their hardest. So it’s very difficult for me to be angry at my biological family, it’s very difficult for me to be mad at my adoptive family because everybody was just doing their best.

But as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. So yes, it’s still problematic, the institution of transnational adoption. There are issues that need to be resolved. But I think the people who are going to solve those are us, and the people who care enough to create that change.

Going back to your story, what were those early years like?

I got hired on an E-2 visa to teach at a hagwon (after-school private academy). I remember moving around a lot because they had to find a spot for me.

Then about a year later I moved to Jeonju. I quit my job with about a month left on my contract. In the States, I had taken a first-year Korean language course and my Korean professor in the States had a friend at church who had another friend who was teaching at Woosuk University in Jeonju and she was looking for a researcher, and so she hired me. I moved down to Jeonju because my Korean family lives there.

It was a very toxic work environment. I think it’s like that in a lot of Korean workplaces. [After an unfair incident due to cultural differences], I basically had to clean the office for 4 months.

It was really hard at the time, but it really taught me a lot about the realities of what it’s like to live in Korea, I think. But I did have a very good support group. I would come up every once in a while, on weekends, and it was adoptees… It very much was having that community here [that helped].

And then moving back to Seoul [after a year], it really helped prepare me for… [Now] talking to my corporate clients and what they go through, their psychology, and even when they cancel and things like that; I really understood that things are out of their control.

When you came back to Seoul, what was your plan?

I spent [about] a month job hunting and then I got a job teaching at an adult hagwon and I did that for about a year and that was also not good, but by then I knew the system. I found out later that [the school] charged less money [for lessons with me because I’m Asian], so I just decided that I was going to do it by myself and that I didn’t really need the middleman anymore. I just started to teach by myself and attract some of the same students and have been doing that for about three years.

Was it difficult to start your own business?

They make it very easy. I got a teacher’s license to teach children. I got the Ministry of Education Approval thing to tutor students. Then I realized that I should get a tax ID. I did have a lot of help from my Korean contacts. I think [people without Korean-speaking support] rely on the Seoul Global Center a lot, [but] it’s very easy to start a business here.

What kind of teaching do you do?

I teach professional business English, and I’m very fortunate because I kind of stumbled into medical devices and pharmaceutical companies. [I do a lot of work with] Johnson & Johnson and Boston Scientific. I also occasionally do some editing work with political science journals.

Can you explain a little bit about how this year has been different (for your business)?

I did have plans to kind of scale up a little bit this year [which was not] feasible. But there’s opportunity as well. You know, with COVID-19, I’ve noticed a lot of Korean people have come back from the States and want to continue their English lessons and they want to focus on academic English. And you know, there’s a lot of word-of-mouth here, so it still very much is one of those cultures.

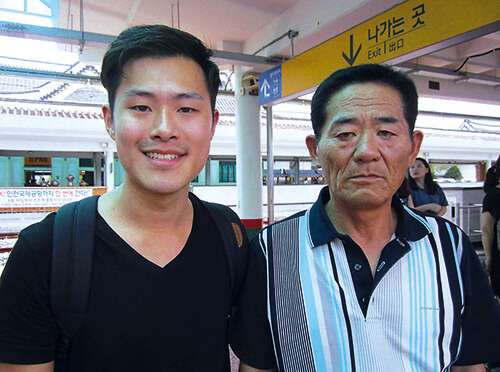

What was your experience like reuniting with your Korean family?

It was about two months after I arrived in Korea that I did the birth search. I was switching to the F-4 visa and so I went to HOLT, my adoption agency, to get the [necessary documents] and they asked if I would like to do a search.

About two days later, they contacted me. They were waiting, my family, so HOLT sent them the telegraph and then two days later I was on the phone with my uncle. It was wild.

I met them officially in August. I made contact in April, but it was months later that I actually went down for the reunion. They took us to the HOLT intake center down in Jeonju.

They took us to the intake center and there were babies there and we played with the babies. It was a lot. I was like, “this is a lot for me to play with the babies while meeting my birth family while being in Jeonju for the first time.”

I did that for about an hour. Then I went upstairs and met my uncle and my aunt. The translator was about an hour late. It was hard, sitting there. We shared pictures for the first 10 minutes. Then the translator came and they told me everything that I knew from HOLT.

Which was?

My birth mother is mentally ill. She’s in the hospital. My mom is one of nine children, a large family. She was living with my grandfather at the time of my birth and she was not institutionalized yet.

She would leave the house for long periods of time and then come back. One time she left and got pregnant and came back. And then by that point, she was about eight months pregnant, they said. With me.

With mental health, people are like, “Koreans are not good with mental health,” but that really has not been my experience here. I think it’s really because of my mother, like in her situation.

I’ve actually had the most mental-health positive experiences in my life in my Korean circles.

How about with your Korean friends?

Well, it’s definitely not without challenges. I mean, some of it is [that I’m] nonthreatening. We’re coming from different perspectives and we’re not competing, [and that] empowers them to be open about what they truly think.

I will say there is a caveat to this. It’s very clear that I’m friends with individual males. I’m never friends with a group. I think that’s by design because I think the values within Korean male group friends is very different from what I would be accustomed to or what I would, quite frankly, tolerate.

You mentioned earlier that you keep in touch with your birth family. How has that relationship developed over time?

Usually every Chuseok or Seollal holiday, I visit the hospital. It depends on the circumstance. Usually, my uncle or aunt takes me with one of their kids. I have four cousins, and they kind of re-adopted me as their fifth child.

With my uncle and aunt and when the whole family is together, [we always speak] in Korean. I did that first year of Korean language class at ASU and then I did my stint in Jeonju and it was sink or swim. I spoke barely any Korean and in two years, you pick up something every day, and that’s kind of how I learned. But that was a challenge, too, because they do speak in dialect, so it was really hard at first.

But when it’s one-to-one, me and the cousins, it’s English. I have a good relationship with the younger two cousins. They try really hard. That’s all I can ask. I try hard. They try hard. We all try hard. And it’s good. I feel very lucky.

It’s interesting. We don’t have the same memories and schema and experience, but I do notice there are some personality similarities. I get a ton from my family in the States, but there are some things I notice that I get from my birth family.

What did you notice that you had in common with your family here?

It’s hard to pinpoint. I’m very extroverted and my family in the States are all very introverted; it’s silent at my house, except for me, my bubbly self, popping around the house or whatever.

Even my adopted brother and sister are very introverted, too, but my family in Korea is very extroverted.

Now you know where it comes from.

Yeah, it’s weird. They’re very extroverted, very warm people. Very sensitive. My family in the States, too – some are also sensitive, but… I don’t know, it’s not the same. These aspects, they feel biological. It sounds really stupid but I was walking down to the train station one time, and I was watching my [cousin] walk down the stairs, and I was just like, “that’s how I would walk down the stairs.”

He had the same walk, you know, the same weird body. (laughs)

Those are the two big ones I notice. Music as well, like my mom really likes music, she sings in the hospital. None of my family in the States is really musical, so that’s another thing.

I feel kind of voyeuristic sometimes visiting them, because they want to show me where they’re from and it’s cool. But it also feels very touristy and I feel almost like they need to impress me a little bit. Like, “we’re not poor.” I think that’s a big sense of shame for them because I’m the adopted one and I think that they feel like they have to show that “our family is not like that” and I want to be like, “it’s fine, I’m not ashamed.”

We go to museums and we do activities. It’s a little active for my style. I’d rather just have a meal and talk about something – politics actually – we’re getting there; we had that discussion actually. (laughs)

You studied political science for your undergraduate degree and international relations for your graduate degree. You also mentioned you’re currently doing a graduate program in linguistics. Do you ever see yourself running for office or seeking an administrative position in education?

I don’t know… Maybe at this stage, no. I don’t know if I’m ready to be in the public eye like that. But changing these institutional problems, especially regarding education, language education, and policy – it’s exciting work. There’s a lot to be done.

Regarding our language policy in (American) schools, I think that’s a big issue. I think we need a better structure, like academic English programs for these [immigrant] kids aside from learning English in content classes and mainstreaming them appropriately; I think there are big issues in Arizona and California specifically. I think our states are at the forefront of that since we are on the border. But I think across the country, the United States, we could be doing more to help our fellow citizens learn the language.

I think we’re seeing that in Korea more and more, too, especially with (multicultural) children and helping everyone mainstream into society and participate as productive citizens. It’s sad that we have these ideologies that prevent people from being fully productive in society. (Diversity) enriches our society.

It’s important work. Especially with diversity – getting that perspective out there and making sure that these stories get told and making sure that we’re heard.