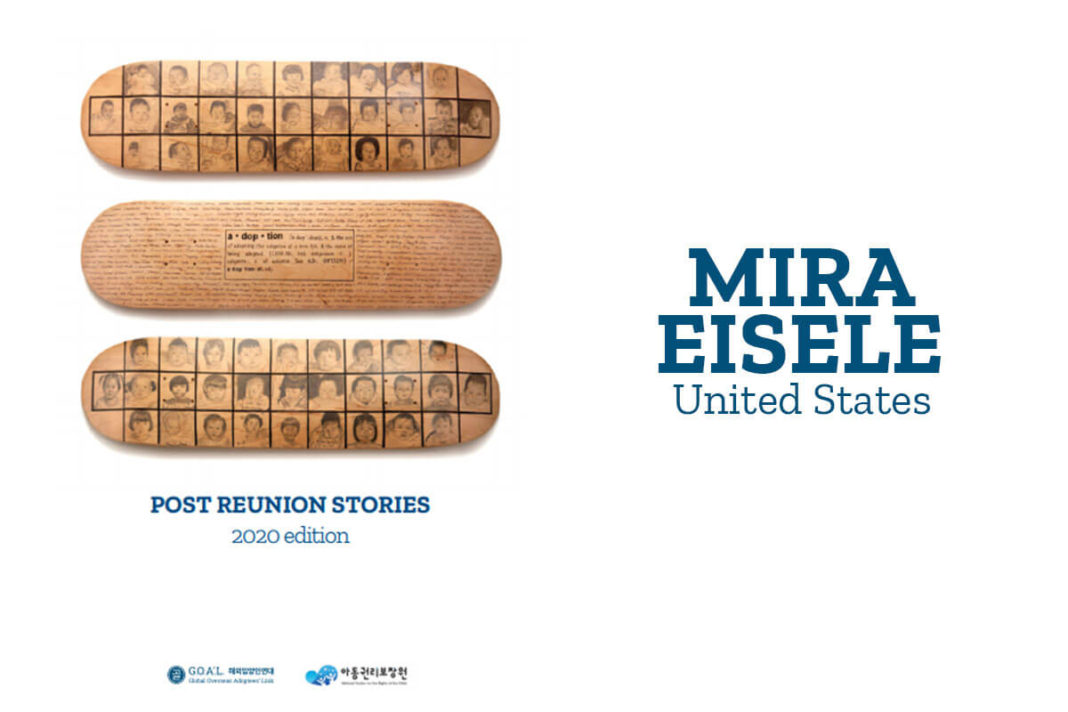

Story by Mira Eisele

Since I was young, my parents here in the United States have done their best to maintain my connection to my Korean heritage: they brought me to heritage camps every summer; our house was full of traditional paintings and pottery; I had a series of Hanboks as I outgrew my old sets; and they made sure every question I ever had about my adoption was answered. I was always able to access, read, and thoroughly digest all the information that was given in my adoption paperwork. My mother would always tell me that my birth mother loved me and wished for a better life for me, hence why I am here. I also maintained a natural curiosity for my biological family, always curious about what kind of people they were, what they looked like, and what their lives in a distant place were like. I lived a classic and very happy childhood. I rarely ever fought with my siblings (who were also adopted from Korea though not biologically related), and my parents loved me more than any child could have ever hoped for. There was seldom a moment growing up where I was touched by sadness or hardship, and I acknowledge that I am truly blessed to have been placed with such a nurturing and caring family.

I began the search process to find my biological family back in 2015, but I decided I was too young—at the time I was only a sophomore in high school. However, in November of that same year, my mom was contacted by my adoption agency. They said that my biological mother was looking for me, and she wanted to reconnect with me somehow. Shortly after, I drafted a letter with the help of my mom to send to Korea along with photos of my life thus far. I sent it, yet I held my expectations back; I didn’t want to get my hopes up too high only to be disappointed by the response or lack of. It was a few weeks later that I received a letter and pictures back. It depicted my mother with her friends and her family: my biological grandparents and her brother. She invited me to come to Korea, saying that she would like to meet me just once. She said that in all those years she had never forgotten about me, and I could feel her devastation at having to send her child across the world. I learned her name for the first time, but I also learned that my Korean name had been chosen and given to me by her. My mom and I were at a loss. We were told that the name had been given to me by a random social worker, and we were both crushed knowing that I had lost a name that was obviously very special to my biological mother.

I travelled back to Korea in the Summer of 2016. I had previously been back to Korea in 2014 with my entire family, but our main reason for going was for tourism and to see mostly the capital city. I travelled with just my mother, and for the first few days we stayed with the adoption agency. I remember sitting in the meeting room clutching a pink notebook that had all my questions that I had written down, knowing that I would forget about them the minute she walked into the room. I was wearing a purple dress that my mom and I had bought just for the meeting so that I could look my best. I remember thinking to myself, “this is the before, and after this meeting, there also be a distinct ‘after’ in my journey as an adoptee. I’ll never forget when she first walked into the room. I can remember every detail about her appearance. I gave her a necklace to match the one I was wearing, and my mom gave her a picture book full of photos of me from when I was young. For a short while, my mother and the translator left the room. My biological mother broke down in tears, sobbing and holding my hands. She couldn’t stop apologizing and telling me how much she had regretted not keeping me in Korea. After the initial meeting, we exchanged Kakao Talk information and addresses before going to get lunch together. After lunch, she took me clothing and shoe shopping. We said our goodbyes at the end of the day, but I also knew that we would be meeting again. She took a train back to Busan (but, thankfully not like the movie!), and we later met for a day or two in her hometown. We ate good food, and we were coincidentally in Busan for my sixteenth birthday. Her and two of her closest friends arranged a small party in a restaurant and prepared gifts and flowers. She wore a large pair of bunny ears and I wore a light up pair of Minnie Mouse ears she had gotten me. My uncle, her brother, is also a pastry chef, so later that night he came back with us to my mother and I’s hotel room and brought a large cake for us to enjoy. I loved every minute of it. We had a very teary goodbye at the Busan train station, and then I left back to Seoul under the impression that that was the last time I would be seeing her during my time in Korea.

However, she wanted to see me as much as possible during my stay, so she organized a trip back to Seoul where she would stay with her sister. I got to meet my aunt and have a meal or two with her and spend more time with my birth mother. She stayed up until my mom and I were at the Incheon Airport, ready to head back to the States. I remember the way that she cried and held me, squeezing me so hard I could barely breathe. She gave me an envelope full of money before I headed back too, and I realized that it was really all she could do to somehow take care of me when I was so far away from her. I cried all the way through security, but I wouldn’t have been surprised if they could have heard my mother crying outside its doors. Perhaps this was a usual scene for them—mothers sending their children abroad, despite the circumstances being much different.

Fast forward a few months later, she came to visit me and my family here in the States for Thanksgiving that same year. We spent about a week together during my break from school. She returned to Korea, and while we have maintained steady communication via social media and Kakao Talk since, I have not seen her in almost four and a half years. I was only just recently able to call her for the first time because my partner speaks fluent Korean. I hold these memories very fondly, as they are bittersweet moments in my life thus far: I was enthralled to be meeting my biological family, yet I was also so saddened to know that I had missed my life with them; I had so many things I wanted to ask her, but I had such limited Korean we mostly talked through our phones’ translation apps (which we were still incredibly thankful for). I found myself not reveling in the wonders and miracles of adoption, but rather hating it for all the hardships that it had put myself, my family, and my biological family through.

Some things that I would like to state regarding my personal experience and my story:

- I do not refer to my family here in the United States as my adopted parents, and I do not refer to my biological family as my “real” family or any other sort of odd “authenticating” labels. My family here is the family that raised and loved me for my entire life (not to say that my biological family did not still think about or love from across the sea), but there is still a large difference between the two.

- My story is unusual from all other stories that I have heard previously, and I was wary to publish anything about my adoption story because of this fact. I do not want other adoptees believing that their story will also be this way or that my story is normal. I am not saying that others’ birth families do not think of them in fondness, longing, or loss, but the situation through which I was able to meet my biological family was not normal from what I have heard through others’ stories. The fact that I was able to meet so many family members and spend so much uninterrupted time with my mother was somewhat unusual. It was also unusual that my birth mother was the one to initiate contact.

- I used to long for the life that I missed in Korea. It was absolutely devastating to see young children and high school students my age walking around the subway heading to school together in their uniforms knowing that this could have been a tangible childhood for me. However, I believe that while this pain is the result of cultural stigma and immense cultural and familial loss, we as adoptees self-inflict further injury by imagining the impossible. There is absolutely nothing that we can do to ever make up for this. Our time that could have been spent having a life in Korea is gone, and it will not be truly and fully compensated by living in Korea, learning the language, or learning everything possible about the culture. By holding ourselves to such a high standard and by constantly trying to prove how Korean we are, we hurt ourselves and exacerbate our wounds.

- I love my families equally, and while I do hold much sadness still concerning my biological family, I am even more immensely grateful for the privilege and opportunity to have met them and to have contact with them.

- Try not to hold resentment for your birth family. Of all the stories that I have heard, the mothers are truly devastated to not keep their children. They live in a society where women like them are constantly under intense social stigma, and the effects of this stigma affect aspects of their life such as education and future employment. Resenting your birth family will only create more pain for yourself, and while forgiveness is easier than rage, we will find more peace within our own persons and identity when we choose to be balanced.

- This is YOUR story. No other person has the authority, the power, or the autonomy that you hold over your adoption story. While perhaps there are figures in your life who will make you believe the opposite, the choice to share your story or to keep it completely private is under your complete jurisdiction. If sharing details of your story and allows you to maintain autonomy or is something that you just feel is right, then trust your instincts. Do not let others hinder you. Conversely, do not ever let someone take away your ability to keep your story private. These are memories and times that are immensely intimate to us, and they should remain that way.

- Do not lose yourself in trying to live up to the person that your biological family wishes you could be. You have already developed into the person you were meant to be. Do not let someone who is, frankly, new to your life interrupt all the progress that you have made. You deserve the self-love you had before to remain untouched by others’ expectations of you.