Aeranwon is a pioneering organization that has dedicated their work to support single mothers raising their children. Their mission to protect life, motherhood, and the family did not see much backing during a time when Korean society thought it would be better for mothers to send their children overseas for adoption. However, their efforts have paved the way for over 60 facilities and networks like theirs to open nationwide.

Aeranwon was founded in 1960 under the name “House of Grace” by missionary Eleanor Vanlierop. She first established a facility to help provide rehabilitation and protection for young women in Korea who were unable to care for themselves. The country was still recovering from the Korean War and circumstances often left young women in critical situations. Teenage runaways, domestic abuse, and early pregnancies contributed to an increase in single mothers. So in 1973, Eleanor decided to commit her work to helping single mothers. “She witnessed the depressing and sad life of the single mothers who had to send their babies to foreign countries,” says Young-Sil. House of Grace was later renamed Aeranwon in 1977 after Eleanor’s Korean name, Aeran, which means “planting love.”

Today, Aeranwon describes themselves as a “one-stop service for single parents” and is the core of Aeran Single Parent Family Network. It is a network of 7 different branches that help mothers at all stages of their pregnancy as well as after birth. But it took them time to develop and receive support from the government to become what they are now. At first, mothers were only allowed to stay at their facility for 6 months. But Young-Sil points out, “they are pregnant for 10 months…when babies are born, [mothers] had to almost immediately leave, so it was basically impossible for them to raise their children back then.” Young-Sil first worked at Korea Welfare Services, and in 1990 when she moved to the Single Mother’s Counseling department, she found that many of the mothers wanted to raise their children, but lacked the support to do so. She was much more interested in helping these mothers keep their children, but working at the adoption agency made it difficult for her to do so.

So Young-Sil decided to leave Korea Welfare Services and she found work at Aeranwon, where they shared the same idea of supporting single mothers and helping them to raise their children. At the time, Korean society still had a very negative view about single mothers. “‘How can single mothers raise kids alone? It is miserable, and kids should be sent to better homes and mothers should just forget them,’ was how people thought,” remembers Young-Sil. She also says how there was a lot of social prejudice against children raised without a father, which led many mothers to believe it was better for their child to be raised overseas and not in Korea.

When Young-Sil joined the staff at Aeranwon, they worked to raise money to support their vision of helping mothers keep their children. They saved money for basic necessities like formula powder and diapers, but later on received funding from the Community Chest of Korea. With this funding, they were able to pay for monthly rent at a small facility where they could have women stay for 1-2 years and receive vocational training. In 2000, they moved into their new facility and quickly found themselves at full capacity with young women who were seeking help to care for their children.

Because Aeranwon provided childcare support, mothers were able to complete vocational training, find jobs, and raise their children. Aeranwon not only helped these mothers keep their children, but they also helped them become self-sufficient while gaining confidence and perseverance. They wanted to create a system, “a system in which the country supports the mothers,” states Young-Sil. So 2 years after Aeranwon opened their first facility, they held a seminar where mothers they had assisted came to speak. “Some moms even came from Jeju Island, their babies piggybacked on their backs.” At the seminar the mothers were overcome by emotion, crying while they expressed the gratitude they had for what Aeranwon was able to do for them. “They talked about how their babies were about to die, and how desperate they were…their kids could have been sent to different homes, but [because of Aeranwon] they could responsibly raise their children.”

Listening alongside others in the audience were Seoul lawmakers and government officials. They heard the stories of the mothers and how, because of Aeranwon, they were able to keep their child and live successful lives after giving birth. It was after this seminar that single mothers’ well-being and the well-being of their children were taken more seriously by the government. Funding from the government was given to provide the building which is now their headquarters, Aeranwon.

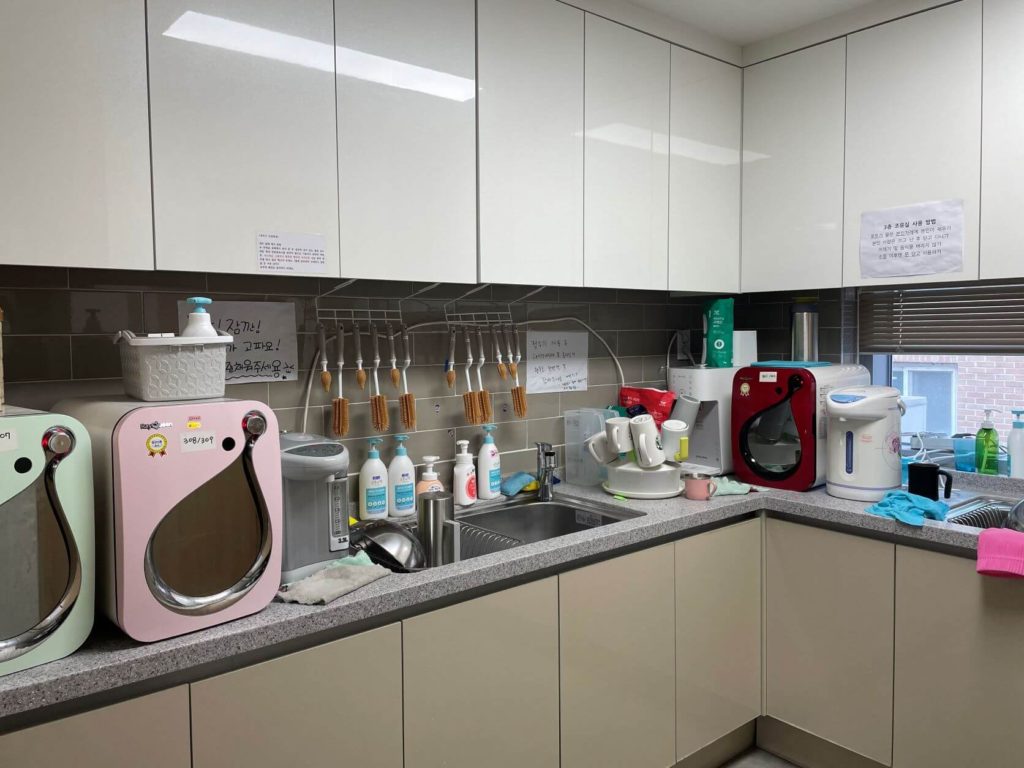

This 4-story building is located in Seodaemun-gu, near Yonsei University, and houses mothers during their pregnancy until 6 months after they give birth. Here, mothers are given pre and post-natal care, counseling for the baby’s future, as well as vocational training for the mother’s future. Younger mothers are also able to complete their high school education through Narae Alternative School, an in-facility alternative school for teen mothers. Young-Sil explains, “like a regular school, instructors come in and give lectures, and there is also a diploma for them.”

Since 2000, there has been an increase in welfare support to aid single parents in raising their children. So these days, Aeranwon mainly helps women who are in extreme situations. “About 70% of the women who come to us live separately from their parents [because of] divorce or they have passed away, so they’ve had a very difficult life since childhood,” says Young-Sil. One of Aeranwon’s current residents, Haeun [pseudonym], talks about her experience at Aeranwon. Haeun grew up with her grandmother in Daegu, but has lived on her own since middle school. She became pregnant and when a friend, who was also a single mother, invited her to live together in Daejeon, she went. However, she was later kicked out and didn’t know where to go. She was still pregnant, so she searched online and found a place for unmarried women, but there wasn’t a lot of information. “I called the 1366 hotline for women (Korea Women’s Hotline) and they told me about [Aeranwon].”

When she first came to Aeranwon, Haeun just cried. “When I heard the name ‘center for unmarried mothers,’ the nuance of it made me feel like I was in a devastating situation,” she remembers through tears. Mothers at the seminar back in 2002 also talked about their anger towards Korean society because of the social prejudice that single mothers face. “At first I was conscious of what other people would think…if they would stare at me for coming into this building.”

But Haeun quickly found out that Aeranwon was a safe place. She was able to feel a sense of community and belonging with the other mothers who were in a similar situation as her. “I’m one of the older residents here and seeing women who are younger than me staying strong made me feel relieved [when I first got to Aeranwon]. I didn’t cry anymore…” She participated in the various programs Aeranwon offers its residents – parenting education, vocational training, and even yoga.

Aeranwon’s network goes further to empower these young mothers and makes sure they are prepared for life after living in their facilities. Haeun also gained confidence that she could take care of her child. “I never thought about giving up my child for adoption,” she says, but she did feel unsure and scared about how she would be able to raise her child. By being at Aeranwon, she was not only supported by the staff, but the other mothers as well. “If you hear stories [from other mothers] like, ‘When you go to the second center after [staying at Aeranwon], they support you with this and this, and help raise your child while you study for your certificate…’ and you just feel like you can raise your child on your own.”

Haeun recalls this time when she was out with some of the other mothers buying baby clothes. “The attendant was making small talk like ‘Oh, you guys are buying gifts for someone?’…and the other mothers were confident in saying, ‘No, we’re unmarried mothers,’ because we had each other.” Since she still lives in the center with the other mothers, Haeun says she hasn’t had the chance to really feel society’s gaze on her as a single mother. “I don’t know how hard it will be, but we talk about it [at Aeranwon]…” Her initial self-consciousness – about what strangers would think of her entering and leaving the building – went away once she saw that other mothers didn’t care. But she also realizes that she hasn’t been out with her daughter on her own, so she’s uncertain about how she will feel then.

Aeranwon offers various programs and educational opportunities that help mothers make the most informed decision when it comes to their child’s future. “Our opinion is that we should base the decision mainly on the child,” Young-Sil says. Aeranwon counsels mothers and says, “the first priority should be to be raised by their own parents, and second, domestic adoption, and third, overseas adoption…last should be to be raised in the facility.” They have mothers meet with other mothers who are currently raising their child, as well as mothers who have sent their children for either overseas or domestic adoption. They even invite overseas adoptees, who are living in Korea, to come to talk with mothers about their experience growing up overseas. If a mother decides on adoption, Aeranwon suggests mothers choose domestic adoption so the child can still have a sense of national identity.

Even though Aeranwon encourages mothers to keep their children, they ultimately leave the decision up to her. They provide resources, testimonies, pros and cons, and other information to assist the mother in making an informed decision about what is best for her child. Whichever decision the mother makes – to keep her child and raise him/her or relinquish the child for adoption – Aeranwon is there to support her decision.

Within Aeranwon’s 7-branch network, they have two different types of centers mothers can go to after their stay at Aeranwon: Aeran Mother & Baby’s Home and Aeran Seumter.

Aeran Mother & Baby’s Home is a center that houses young mothers and their babies, while focusing on teaching mothers to be self-reliant and help prepare her to raise her child. Here, mothers receive continued vocational and employment support as well as classes in parenting and life skills. “The atmosphere of the center itself makes mothers realize that they can raise their children because help is available, says Haeun.

Aeran Seumter is a center for mothers who have made the decision to give their child up for adoption. While they also receive vocational and employment support, they also go through grief counseling. “Before the year of 2000, about 80-90% of the cases [single mothers] led to adoption,” Young-Sil says. Even if women wanted to raise their children, they did not have jobs or a place to live so adoption seemed like the only option they had. But as facilities like Aeranwon began to receive support from the government, about 80% of the mothers that came to them made the decision to raise their children on their own.However, as the years went on, Aeranwon also saw an increase in mothers with mental health disorders who were not prepared to raise their child, which led to adoption. This led to about 60-70% of the mothers who come to Aeranwon choosing to raise their child.

While Aeranwon currently focuses on the welfare and support of single mothers, they hope to redefine the definition of “single mothers” in Korea. “I think the word “single” should not be misused,” explains Young-Sil. Throughout the years, as they have worked with single mothers, they have come to find that there are many “social blind spots” in the system. There are mothers who are married, but live in poverty or some mothers who are divorced, as recent as 3 months after marriage. The government does not give aid in these situations, since they were once married. “I think there is too much focus on whether the mother is married or not,” continues Young-Sil. “What the government should actually know is that adoption, child abuse, and the need to go to facilities [like Aeranwon]…start from a crisis pregnancy. And a single mother is not the only one who is in crisis.” Young-Sil would like to remove the word “single” from the label of those they help. She hopes that Aeranwon will be able to operate as a facility where any person who is experiencing a crisis pregnancy can come in and receive support. “I think we need to expand our scope to help women in crisis situations so that they can keep their children, and to provide welfare for children.”

Young-Sil does not want to just limit Aeranwon’s services to women. When asked about opening a facility like Aeranwon for single fathers, she recognizes the need. “We should start such a system… but there should be male personnel…[to handle issues more related to the fathers’ situations].” She also notes that just as the government did not provide welfare for single mothers back in 2000, now they do not help married or foreign mothers. “Most of them [mothers not supported by the government] just give up their children like single mothers did in the past. They are now abandoning their children in the baby box. This is because there has been no support for women in a crisis pregnancy.” So moving forward, Aeranwon is working to expand their reach of people who can receive their services.

Haeun’s daughter is now 6 months old and they are getting ready to move to Aeran Mother & Baby’s Home. “Because we know we have places to go after we leave here [Aeranwon]…and places where we can reach out for help to gain self-sufficiency, we are relieved.” Haeun is studying to become a nursing assistant. She is also working towards obtaining a certificate for proficiency in computers and has plans to work at a doctor’s office. “I like going to the mountains…I like to spend my time hiking,” she says and now that her child is old enough to attend daycare, she has more time to pursue her studies and enjoy some of her hobbies.

During her stay at Aeranwon, Haeun also encountered mothers who have made the decision to relinquish their child for adoption – whether domestic or overseas. She says, “…they give birth to children without giving up and put them up for adoption with broken hearts.” She can see this decision was not an easy one to make and that the parents of overseas adoptees from the past “might have felt the same…when I see these mothers I can feel that they’re heartbroken.” Aeranwon encourages these mothers to write letters to their children, letters that will be sent with them when they are separated. You can read a letter written from another mother at Aeranwon who made the decision to relinquish her child for adoption.

AERANWON

Aeran Single Parent Family Network

Website: www.aeranwon.org

Address: 138 Yeondaedongmun-gil Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, South Korea

Email: aeranwon@chol.com