Oftentimes, overseas adoptees grow up with similar narratives, and questions throughout their adolescence: “Why was I adopted?”, “What if I was adopted to a different family?”, “What if I had not been adopted at all?”

In this series, we meet Choi Soonyoung (최순영), a domestic adoptee from Pyeongtaek, South Korea who helps us explore a different question that might not have crossed many overseas adoptees’ minds: “What if I had been adopted to a family in Korea?”

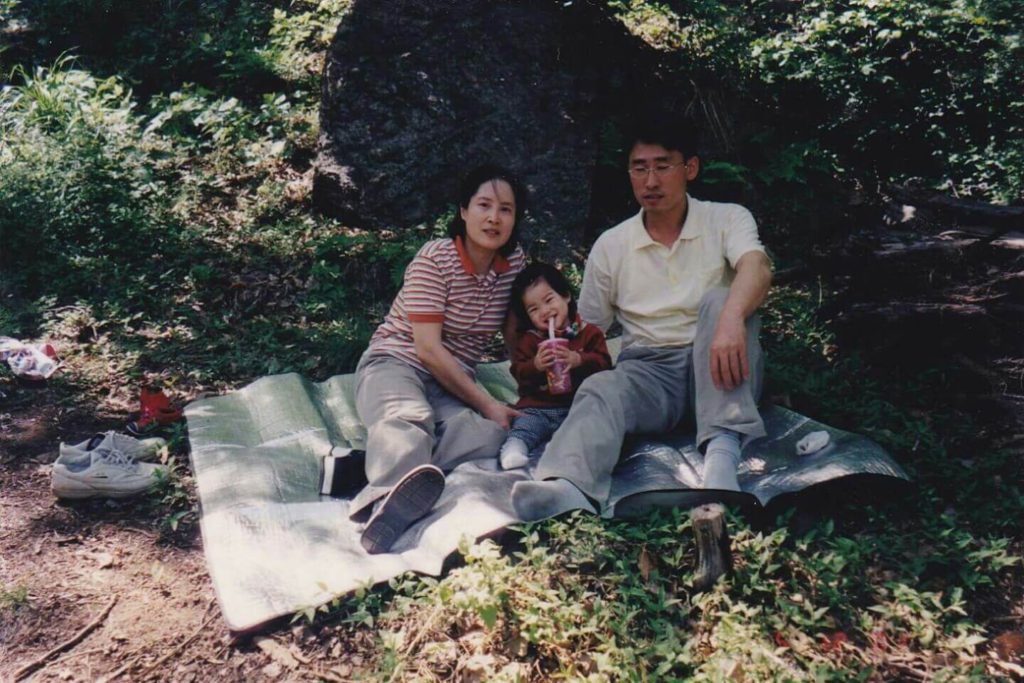

Choi Soonyoung (최순영) was born in December 1999 and was adopted at 5 months old. Her story starts in a way that many other adoptees can resonate with. She was found abandoned in a police station garage, wrapped in a blanket in the middle of December. It was so cold that her face was turning purple. The police officers who found her took her to the hospital. At the turn of the millenium, there were so many babies in the hospital that the staff was unable to take care of her. One of the officers jumped in and began giving her some milk. Since she was freezing and starving, she drank it really well. The officer looked down at her while she ate and later told Soonyoung, “I fell in love with you at first sight and wanted to adopt you.” That was the first time they met, and that officer eventually became her father.

Sometime after she was adopted, Soonyoung’s parents wanted her to have a younger sister. Even though they were planning to adopt a girl, they adopted a baby boy who was around 7 months old. Around 2 to 3 years later, they adopted another boy, and then another, and finally, a sister came when she was 8 years old.

On the way to meet her second brother, Soonyoung recalls her parents being very nervous in the car. Her mother’s hands were shaking while she drove, and Soonyoung was in the backseat with her father. He took out a big sketchbook and began to explain how she was born to another mother who couldn’t take care of her, so she came to their home, and they became a family. At one point, she recalls thinking that adoption was “I go someplace and meet a baby, and he comes to our home and doesn’t go back. He just calls my parents his parents.” She didn’t feel adoption was a strange thing; in fact, she thought all people became families through adoption.

When Soonyoung was 8 years old, her friend’s mother was expecting, and this was her first time seeing a pregnant woman. She found it really strange and awkward. Even though she knew she was adopted, she kept asking her mother, “Am I from your belly?” She really wanted to hear that she was also from her mother’s belly, but her mother said, “I had you from my heart.” She was so confused. “Can a baby grow in your chest?! How can a baby come from a heart?” she laughs. “It was quite awkward. I think I came to learn about my adoption from that time. I mean, I thought I was a little different, and there was a difference between being born and being adopted.”

For many families in Korea, it was not common for them to be open about adoption. Soonyoung goes on to clarify, “There aren’t many [domestic] adoptees in Korea, and before 2000, Korean people adopted in secret.” However, her parents didn’t want to be secretive as they were happy to meet her [because of] adoption, so they were open and told others at their church. After meeting her family, 8 other families also adopted children. She also participated in a lot of meetings for adoptive families. There they learned how loving and good adoption was for them, so she wanted to share this with others. She says, “Adoption was really good when I was young.” She was proud of it and wanted to let everyone know.

Therefore, it came as a shock to her when other people didn’t perceive it in the same manner. Soonyoung told the lady who cut her hair that she was adopted, but the lady was surprised and gave her an uncertain reaction. She also remembers attending a hagwon, where it was common for friends to share secrets. She would say, “I have a really big secret… I’m adopted,” and her friends were really surprised. At first, they didn’t know what adoption was; they just thought it was having a “new mother.” Some of her friends were worried about her and would ask things like, “Are you doing too many chores?” This was one thing Soonyoung didn’t think about: how all the stepmothers in fairy tales, like Cinderella or Snow White, are mean. But some kids would say, “New mother? That’s not real.” After hearing this, she felt sad and didn’t want to tell her secret anymore.

Soonyoung talks about how even some of her grandparents didn’t think adoption was good, and they didn’t understand why her parents adopted so many kids. “Although you adopt them and raise them with love, they will betray you when they become adults,” they would say, even with her sitting right next to them. She would assure them by saying, “I won’t.” However, because of these negative reactions, she stopped talking about being adopted at the age of 12.

What does adoption mean now?

There were two turning points in Soonyoung’s life that helped shape her current outlook towards adoption. The first was during a domestic adoptee camp. She went to a center where birth mothers were about to relinquish their children for adoption. She felt uncomfortable being there, especially because the adoptees had to write letters to their own birth mothers. She had nothing to say at first because she didn’t have any good emotions about her birth mother. She blamed her birth parents for all the negative emotions she had begun to feel about adoption and thought, “It’s all because of them that I get hurt like this. [My mom] gave birth to me, but she couldn’t take responsibility [for me].” She began to realize that she might be angry about her adoption. During this camp, she met 5 mothers who cried a lot while looking at her and told her, “I hope my child will grow up well. I hope my child also meets good parents.” This made her think, “Maybe my mom was thinking the same thing,” which made the feelings of anger and sadness that she had go away.

The second turning point came when she was 12 years old. She met a friend who had stayed at the same facility she was in (prior to the finalization of the adoption process). While Soonyoung was adopted at 5 months of age, her friend stayed in the facility until she was 7 years old. “I was adopted and my life is good, but there are many whose lives aren’t. I thought many kids don’t get adopted or go overseas, so I have to think again about what adoption is to me. Is it good? Is it bad? How can I define myself?” This self-reflection continued well into her adolescence where her biggest issue was wondering, “Am I worth it to have a family?” She began to reflect about when she was young and how she “wanted to prove her worth to other adults… I obeyed my parents [and] I was a really good girl.” She thought, “I have to let my parents feel like it was a good decision to adopt me,” but this was a lot of pressure for her. As she grew up, Soonyoung realized, “I don’t have to prove to [my parents] that I am worth being a member of my family.”

Views of Domestic Adoption in Korea

When asked about the fantasy that some overseas adoptees have of staying in Korea, whether adopted or not, she discusses how “it’s not really good just staying in the orphanage.” She says, “When the children in the orphanage become 20 years old (Korean age), they have to leave with just a little money. I heard it was 5,000,000 won (roughly $4,542.00), and they have to find a home. The problem is that people who [leave] the orphanage put their money together and live together again [with each other]. But, in that place, a new baby is born.” So this situation can continue the cycle of another child being put up for adoption or into the foster care system.

Soonyoung acknowledges that even though Korean culture still doesn’t really understand adoption, most domestic adoptees usually have a good relationship with their family, but not all adoptees are able to have that sort of relationship. There are extreme cases where some adoptees even run away from home. While many adoptees accept the fact that they are adopted, others, including herself, think about adoption a lot throughout their life.

Soonyoung feels one big challenge is how Korean news, dramas, and movies portray adoptees in a negative way. Usually characterized as criminals or psychos, the media shows that adoptees will easily betray and abandon their adoptive family. In dramas and movies, if adoptees know their birth mother, they will leave their adoptive family to be with their birth mother, which is something even her own grandparents worried about. Now she talks publicly about her adoption and creates YouTube videos with her brother. She has even given a talk on Sebasi (similar to TEDx Talks) that has received 40,000+ views and works with other TV programs to change and challenge these perceptions in Korean society. There are adoptees, like Soonyoung, who are trying to improve society’s negative perspective of adoption on social, national, and personal levels through various campaigns, such as National Adoption Day, and other media provisions.

Although there is this stigma of betrayal for domestic adoptees, Soonyoung notes how it’s natural to be curious about one’s biological information, and that adoptees (domestic or overseas) should not feel guilty about having this feeling. She encourages all adoptees to search if they want to, but she acknowledges that sometimes one cannot get the information he or she desires. However, the process of trying can be positive and help him or her grow.

Soonyoung says that she doesn’t have a pressing desire to find her biological parents (right now), but that one day “If I can, I want to try.” These days, she does think about her birth mother and doesn’t want her to be sad. “Like when it’s December, when my birthday is coming. If she feels sad about [me], I don’t want her to be sad because I’m living a really good life with my family.” She says she would like to tell her biological mother this if she has the chance, and she also wants to learn about her birth or more about her biological information. Even though she hopes her birth mother does not worry about her, she can’t help but feel her own sadness in December when her birthday is near. While she was able to meet her adoptive parents on that day, the reality is that she was also abandoned on the same day. “I was on the street, and I was freezing, but I did not cry. I could have cried, but nobody could have helped me. For 11 months, I feel really good, but when December comes…I think about how I would have felt at the time [of abandonment] and I feel a little sad.” Even at the young age of 21, she is reflective on such memories; “I want to keep finding myself because those memories keep affecting me. I don’t know for certain if the memories are affecting me during this [specific] time, so I want to search about what it means to me and how I feel about it.”

From happily sharing her “big secret” with others to feeling anger towards her adoption and everything in between, Soonyoung believes that having an adoptee community to support her and her family has been really important in understanding her own adoption. The community is good not only for adoptees to grow up in, but for their adoptive parents as well. She recalls a time when she was about 3. “I said, “I don’t like you,” to my mom… And her mom went to the community and was crying and said, “My daughter doesn’t like me anymore!” The parents reassured her mother that it would be okay.

However, Soonyoung’s biggest support seems to come from her family and their own willingness to be open about adoption. This can be one of the “biggest problems in domestic adoption” amongst families: secret vs open. “Some families told [their kids] they were [adopted] when they were 15-20 years old.” Because her family was open from the start, it really helped her. “When we grew up, we had problems, but we overcame them and worked together as a family.”

Her mission is to assist adoptees as they explore their unconscious feelings and help them navigate similar issues that she has experienced. “Adoption is my life right now, and I don’t want to hide it.” For this purpose, she is majoring in youth education and counseling.